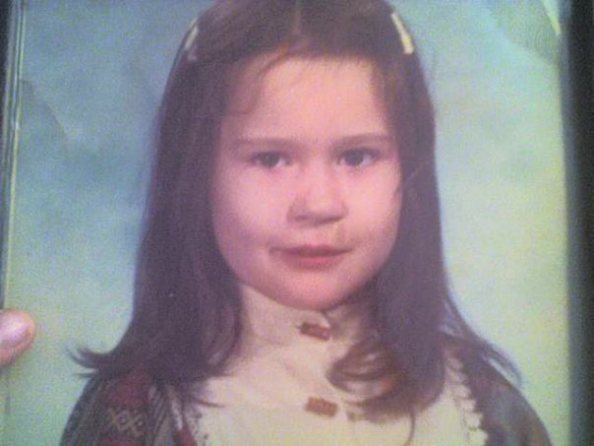

(The author at age 6.)

(The author at age 6.)

The story of how and when I knew I wanted to be a writer is one that I often share with students in my College Composition courses. It is the story not only of my first grade teacher, Mrs. Jackson, but a story that emphasizes the value of student-teacher connectedness and of the far-reaching power that simple acknowledgment and validation in the classroom can have—in short, a story that may have resonance for us all.

I started my first grade year armed with the preconception that Mrs. Jackson was not ‘nice.’ I believed this to be true because it had been whispered among my classmates, and my older brothers had memories of Mrs. Jackson (whom they had dubbed “Action Jackson”) being especially strict and punitive in the classroom. Though I did not know this at the time, Helen Jackson had been teaching elementary school for decades—an astonishing track record, when you think about it. She was a literal personification of the ‘old-school’ teaching mentality, having taught at a time when desks were still bolted to the floor and when all students quaked under the authority of their teachers. On the very first day of class, in preparation for an exercise in penmanship, Mrs. Jackson marched up and down the rows of desks, barking “Heads up! Backs straight! Bottoms out! Feet flat on the floor! Pencils ready!” (This was her mantra, I soon learned, and I can still here her giving these directives whenever I start to slump at my work desk today.)

I should insert here that I was not exactly your run of the mill kid. Already pegged with a Gifted and Talented label at a time in our pedagogical history when no one really knew what to do with Gifted and Talented kids, I was in my own reading group and had privately begun to write stories that I shared with my mother at home. As you can imagine, my Language Arts reader (entitled Helicopters and Gingerbread and chockablockwith monosyllabic stories of Jill and her brother Bill) was dull for me, as were our writing assignments, which mostly involved rote spelling and vocabulary lists. For the first week of classes, I went along gamely with Mrs. Jackson’s simplistic exercises, but during our second week I decided to take a gamble and do something different.

The result was an original short story—written on three sides of wide-ruled yellow paper—called “The Fairy and the Lamb.” The gist of the narrative was this: A fairy had lost beloved lamb but never gave up her search for him. At the story’s stunning denouement, the fairy—surprise, surprise!— is finally reunited with her lamb. The last line went more or less as follows: “The lamb was old and fat, and his white coat had turned gray with age. He didn’t look like the lamb she remembered. But the fairy still loved him with all her heart.”

At some point during the day—perhaps during lunch, which Mrs. Jackson always ate at her desk with a stack of papers before her—my teacher must have looked at our vocabulary drill exercises, for when we came in from recess she had an announcement. Addressing the class, she said, “Jan has written a short story, and it is very good. I would like to read it to you.” I felt a great mixture of embarrassment and delight and tried not to squirm in my seat when the other children swiveled around in their chairs to look at me. I kept my eyes glued to my desk as Mrs. Jackson read the story out loud, but when she got to the part where the lamb was old and fat but the fairy still loved him, her voice grew thick, and I looked up to see her wiping away a tear from behind her bifocals. “Isn’t that sweet?” she said, glaring meaningfully at my classmates, who were far too young to understand that they’d just heard a tale about age and change and the vast pull of unconditional love. But I wasn’t worried about what the other students thought. All I could think was: I made Mrs. Jackson cry—not a bad cry, but a good one, like when my mom cries at the end of every episode of Little House on the Prairie! This was a heady, exhilarating feeling, and an addictive one. It was then, in that defining moment, that I knew I always wanted my words to elicit feelings in other people.

Once I knew I had a receptive audience of one, the stories poured out of me, and sharing my writing with Mrs. Jackson seemed to draw us closer. I would not like to say that I was her favorite, but I know that she held me in special regard. Many years later, when I was living in New York City and was enrolled in my Masters of Fine Arts program, my mother spotted Mrs. Jackson at a local supermarket, and my former teacher—now so old that the fact she could shop on her own was impressive—asked, “How is Jan? Does she still write stories?” When my mother told her I was working on my first novel, Mrs. Jackson reportedly beamed and said, “I knew it! I always knew from the very beginning that that girl would become a writer!” A few months later, Mrs. Jackson’s obituary appeared in the Kennebec Journal. Though she did not live to see my first two books published, I am glad to know she had she was able to get this confirmation of her early hunch before she went on to whatever world lies beyond this one.

The story of Mrs. Jackson and my early experience with storytelling reminds me of many things now as an instructor of writing. It reminds me that simple praise can have a profound effect on learners of every age. It reminds me that the written word can forge connections between people and cement a respect that can last for the better part of a lifetime. It reminds me, most importantly, that one of the greatest gifts you can give to students is to highlight their strengths. The joy of teaching comes from watching them bask in this light and then, with an almost incandescent confidence, to run with it.